The story of how Lincoln became the capital of Nebraska is often told. The territorial capital in Omaha was moved to the village of Lancaster after South Platte politicians successfully won a long and bitter fight over the location of the capital of the newly-admitted state. The name of Lincoln was a last-ditch effort to stop the move. It’s an amusing anecdote today about how Lincoln got its name to troll copperheads. The men behind this story are generally not well-known today. The key player was a high-society darling, the founder of Dundee, the namesake of Happy Hollow, and a maligned figure in one of the most controversial elections in American history.

John Nelson Hays Patrick, called J.N.H. Patrick or Nelson Patrick, was born in Brandenburg, Kentucky, on June 28, 1827.1“Most Interesting Life Story of a Passing Pioneer,” Omaha Daily Bee, Feb. 5, 1905, p.9 He was an early pioneer in Nebraska, and was quartermaster of Nebraska’s volunteer regiment at the outset of the Civil War. An attorney with many business interests, Patrick was a wealthy landowner and prominent citizen of Douglas County. Originally residing in Omaha on Davenport St.2The block is now a downtown parking garage, Patrick moved west and built an estate which came to be known as Happy Hollow.3The home, located at present-day 400 Happy Hollow Blvd., would be sold after his death and the land converted into the Happy Hollow Country Club. When the club moved west in 1922 they sold the land and the mansion to Brownell Hall (now Brownell-Talbot), where the school remains to this day. The mansion/clubhouse was torn down in the 1960s. He would later hire the Shannon Brothers of Kansas City to build more homes nearby, creating a subdivision known as Dundee Place.4History/Architecture – Dundee-Memorial Park Association The Village of Dundee grew out of this subdivision, until it was eventually annexed by Omaha in 1915.

Patrick and his wife were mainstays of the Omaha society pages, and Happy Hollow was a frequent gathering place for the well-to-do. In later days, little was mentioned of his political life, save for his friendship with Sen. Charles Manderson, and the occasional remembrance of Patrick’s brief but eventful time in the Nebraska Senate.

Statehood and Lincoln

In 1867, he was elected to the Nebraska Senate as one of two senators from Douglas County.5Isaac Hascall, later President of the Senate during the impeachment of Gov. David Butler, and eventually a Republican candidate for Mayor of Omaha against James Boyd, was the other. The special sessions called by the Governor had to deal with a number of significant issues, the most pressing of which was the admittance of Nebraska as a full-fledged member of the Union.

In preparation for statehood, Nebraska had passed a state constitution in 1866 and organized this Legislature under that Constitution. The first session of that Legislature met in July 1866, primarily to elect U.S. Senators.6Hence why, despite the fact that Nebraska would not be admitted to the Union until March 1, 1867, Nebraska officially considers the members of the first two sessions of the Nebraska Legislature to be members of the State Legislature and not the Territorial Legislature, which had not yet dissolved and in fact met between the first and second sessions of the State Legislature. The problem was that Nebraska’s Constitution limited the franchise to “free white males.” Congress had already passed the Fourteenth Amendment, guaranteeing citizenship and equal protection under the law, and were not about to admit a new state into the Union that explicitly denied the right to vote based on color. So when Congress passed a bill admitting Nebraska as a state, it was with the condition that Nebraska not deny the right to vote and the Legislature assent to the condition. Andrew Johnson, who opposed equal voting rights (and equal rights of many other kinds) vetoed the bill, which Congress then passed over his veto.7I don’t really have anything to add here, other than Andrew Johnson sucked. The 2nd Legislature convened in order to deal with this condition and allow Nebraska to be admitted as a state.

James E. Doom of Cass County8Comics nerd that I am, I have as yet been unable to ascertain whether Sen. Doom held a doctorate. introduced the bill in the Senate to affirm Nebraska’s acceptance of the conditions. Isaac Hascall of Omaha, who had been elected as a Democrat, announced that he would become a Republican, and sided with the Republicans in favor of the bill.9“The Day We Celebrate,” Nebraska State Journal, May 25, 1892, p.4 Patrick did not arrive until the next day to present his credentials. The official record tells an incomplete story, in large part because the minority report was defeated and not printed. Thomas Majors, who would later serve as Congressman and Lieutenant Governor, objected to the report as “an ungentlemanly document.”10Senate Journal of the State of Nebraska, 2nd Legislature, Feb. 21, 1867. But it seems clear from the context on votes taken that Patrick was firmly on the side of his fellow Democrats, against the condition.

Days before the 2nd Session of the Nebraska State Legislature convened to assent to Congress’ condition, the 12th and final session of the Nebraska Territorial Legislature adjourned. The scene that unfolded during the closing days set the stage for the 3rd Session and the removal of the capital from Omaha. Far from the partisan split over statehood, the loyalties in the final Territorial Legislature were entirely along sectional lines. Tensions came to a head over an apportionment bill which would have taken a seat from North of the Platte River and given it to South Platte. Members from Otoe County opposed the bill because it also would have reduced Otoe County’s representation. A rumor spread that the change was meant to shift the balance of power south so the capital would be removed from Omaha. The vote was deadlocked until the Speaker was removed and another representative from Otoe sworn in, allowing for the defeat of the bill. Members brandished revolvers, the Speaker drew his pistol, and the Sergeant-At-Arms drew a sword.11“The Legislative Imbraglio,” Nebraska Advertiser, Feb. 28, 1867, p.2 The bill was defeated, but the episode would ultimately lead to the removal of the capital in the next session of the State Legislature.

One member of the Territorial Council in 1867 was Mills Reeves, who was also a member of the State Senate, and the same Senator who introduced the “objectionable” and “ungentlemanly” minority report opposing the statehood conditions. Born in Ohio and raised in Indiana,12Where he would return in 1870. Reeves was a staunch Democrat and according to many accounts a former slaveholder. But as a member of the Territorial Council in 1860, he voted to prohibit slavery in Nebraska Territory and objected to territorial Gov. Samuel Black’s veto of the measure, casting it as the right of Nebraskans to govern themselves on the question.13Nebraska Advertiser, Jan. 26, 1860. The Nebraska Advertiser was an early territorial paper published by Robert W. Furnas, later elected Governor of Nebraska. He was not a member of the Territorial Legislature the next session when the body successfully overrode another veto to abolish slavery in the territory.14The tenor of debate being so heavily slanted in favor of abolition, Democrats were left to argue instead that slavery did not exist in any meaningful form in Nebraska, and that those who were with their masters were there voluntarily. This was a laughable and insulting argument, made most prominently by George L. Miller, publisher of the Omaha Herald and member of the Territorial Council. Black as territorial Governor argued that the body had no authority to ban slavery. He resigned not long after the ban on slavery passed.

But whatever expediency caused Reeves to cast his vote in favor of abolition, it did not signal any allegiance or admiration for the man who had become synonymous with the cause, even after his death. He reportedly “hated the name Lincoln ‘even more than he could that of Satan,'” and thus was seen as a potential target to divide the South Platte delegation on the question of removal by means of political trickery.15“Abraham Lincoln’s Connection With Nebraska,” Lincoln Journal Star, Feb. 10, 1974. The Third Legislature was called into special session by Gov. Butler in order to deal with a laundry list of issues the newly-admitted state needed to address. Chief among them were apportionment, and the location of public buildings, including the Capitol.

William Presson of Richardson County introduced the bill to relocate the capital. The bill as written contemplated the eventual location of the capital in Lancaster County, though it was more broadly written than that. Unfortunately, the chosen name for the city was “Capitol City,” which in addition to being grammatically incorrect, was also as Patrick described it, “inexplicably clumsy and ugly.”16“The Story Behind Lincoln’s Namesake,” Lincoln Journal Star, Apr. 10, 2011. The votes on various amendments to the measure were failing on 8-5 votes, so Patrick thought to divide the Republican majority from South Platte Democrats like Reeves who were the floor leaders on the bill. He moved to replace “Capitol City” with “Lincoln,” thinking Reeves would object. But Reeves instead seconded the motion, which was adopted. The rest is history.

And that’s the extent of Nelson Patrick’s place in the common narrative of Nebraska history. He didn’t serve in the Legislature again. Few sources even make the connection between the Senator and the founder of Dundee, except in passing mention of Happy Hollow. But it was his involvement in two scandals, one comparatively minor and the other unlike anything the country had ever seen, that has become largely forgotten.

The Howe Investigation

We’ll start here by saying that the facts are not definitive. A large number of the sources of these accusations are highly partisan or colored by personal rivalries. And where personal rivalries and late-19th century Nebraska politics are concerned, you can bet that chief among the highly partisan individuals involved was Edward Rosewater, publisher of the Omaha Daily Bee. I’ve discussed Rosewater quite a bit here before, and there’s not a lot to add. While he was a prominent Republican, his allegiances were more often than not driven by personality than anything else. He was distrustful of Republicans like Church Howe and Thomas Majors, and his admiration of Charles Van Wyck ultimately led him into the Populist camp for a short time. He was staunchly anti-prohibition, which undoubtedly contributed to his paper’s later relationship with Omaha political boss Tom Dennison.17For much of the Dennison era, the paper was controlled by Edward’s son Victor, after Edward’s death in 1906.

It was Howe who became the target of the first accusation. The Central Nebraska Press of Kearney on Feb. 17, 1876, reported: “Mr. J.N.H. Patrick of Omaha, went to the Capitol of the state last winter with nearly $100,000 in his clothes for the avowed purpose of buying his way into the United States Senate from Nebraska.”18Nebraska Advertiser, Feb. 17, 1876. The allegation was that Patrick paid $3,000 to Howe and $10,000 to Speaker Edward Towle. Howe had not yet made his reputation as a Republican. In fact, some sources at that time still referred to him as a Democrat and in 1876 he was elected as an Independent.19The Independent ticket in those days was in most cases a precursor to the Farmer’s Alliance, Greenback, and Populist movements. In Howe’s case it was most probably a means to get elected when he failed to get the nomination at a Republican convention. The Press also alleged that the Bee would receive a bribe for excusing Republicans to vote for the Democrat Patrick. If the Bee was party to any of this, it doesn’t seem to have surfaced in any of their reporting. The bribery charges against Howe specifically formed the basis of Rosewater’s frequent attacks over the next two decades, and more immediately the basis of what the Nebraska State Journal and other papers dubbed the “Howe-Rosewater Investigation.”

A Senate committee found no evidence for the charges, while Rosewater attacked the committee as a whitewash. But Howe was the only person to vote for Patrick, and what later transpired gives us ample reason to believe Patrick had no scruples about bribery, though his effectiveness may be questioned.

“Secure Your Point At All Hazards”

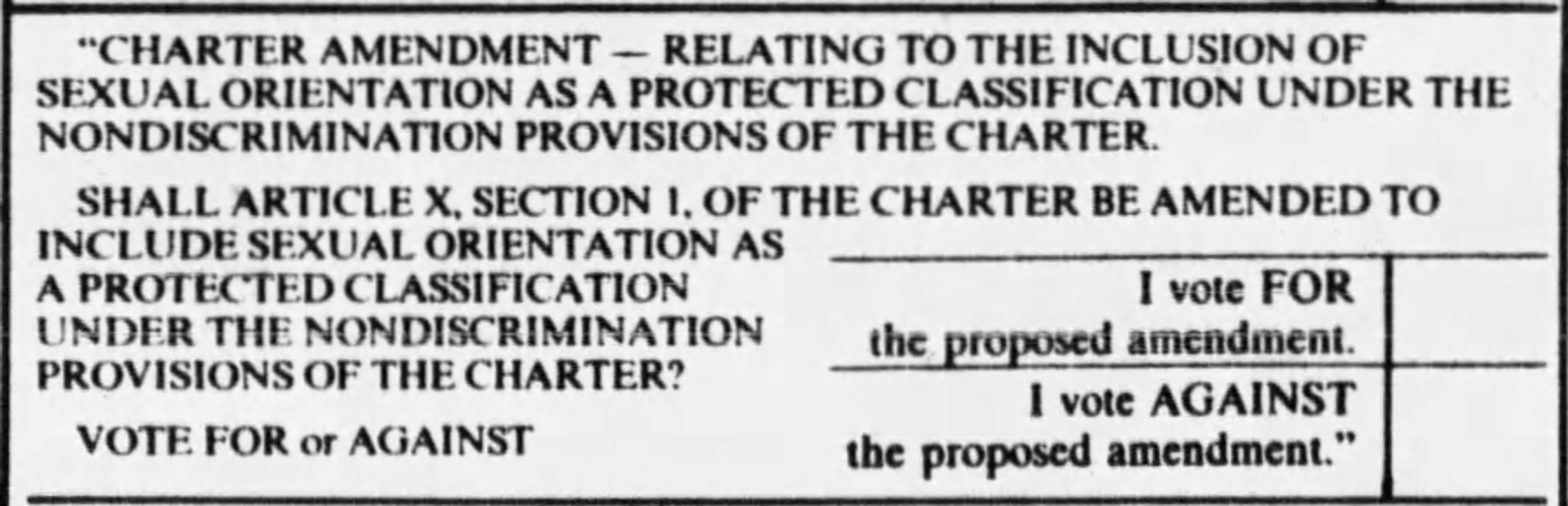

The 1876 Presidential election remains the closest contest in American history. Incumbent Ulysses S. Grant did not seek a third term as President, and Ohio Governor Rutherford B. Hayes was the Republican nominee for President. Samuel J. Tilden, the Governor of New York, was the Democratic nominee. The contest remained in doubt in December 1876, with up to 20 electoral votes contested, but the long and short of it is that Tilden was one vote shy of the Presidency. And Tilden’s allies endeavored to get it for him by any means necessary.

The New York Tribune published decoded telegrams sent between Tilden’s residence and various Democratic Party officials. The telegrams detailed a plan to secure Tilden’s election in several of the contested states. In Florida, the plan was to bribe election officials. In South Carolina, to purchase the votes of several state legislators and imprison Republican electors. And in Oregon, to secure a single electoral vote for Tilden by bribing Republican electors to accept an illegitimate Democratic elector in the state.20“The Cipher Dispatches,” New York Tribune, Nov. 12, 1878.

One of the earliest and most infamous of the messages to be decoded was signed “Gobble,” or “Gabble,” the translation of the cipher showing that it was purportedly from the Governor of Oregon to Tilden himself, guaranteeing to decide the case of a disputed electoral vote for the Democrat. These dispatches came into the hands of a Senate committee in early 1877, and through testimony a relatively complete picture of the Oregon conspiracy came into place.

William T. Pelton, Tilden’s nephew and a resident of his home at 15 Gramercy Park, New York, began communicating with George L. Miller, a prominent Democrat in Omaha and publisher of the Omaha Herald, on efforts to affect the result in Oregon. Miller, unable to go himself, delegated the responsibility to Patrick, who he put in touch with Pelton and Sen. James Kelly of Oregon. “Secure your point at all hazards,” a co-conspirator wired Patrick, admonishing him to keep communications secret.

Patrick wired Pelton with the plan, the translation of which read as follows:

Certificate will be issued to one Democrat. Must purchase Republican elector to recognize and act with Democrat and secure vote and prevent trouble. Deposit ten thousand dollars my credit Kountze Brothers, 12 Wall St. – J.N.H. Patrick

I fully indorse this. – James K. Kelly21“The Cipher Dispatches,” p.37

The “Gabble” message from Gov. Grover to Tilden followed a couple of days later. “I shall decide every point… in favor of the highest Democratic elector,” the decoded message said. The Senate committee determined that this dispatch was actually by Patrick’s hand.221 Cong. Rec. 565 (1890). The plan was clear: replace a Hayes elector who had been constitutionally disqualified by reason of holding a federal office with a Tilden elector, and bribe a Republican elector to recognize the Tilden elector as legitimate. Without the second part of the plan, the vote would remain in dispute and Tilden would be no closer to winning the presidency than he was previously.

Sen. Kelly after the translations surfaced denied any knowledge of their true contents, saying he believed the money to be for legal fees. The initial plan proceeded, with the next-highest Democratic elector appointed by the Governor to take the place of the ineligible Republican elector. The Hayes elector had since resigned his federal office and the Republican electors, by Oregon law, appointed him to the vacant post. It is unknown whether there was any realistic chance of the bribery being successful, but in any case, the money arrived too late to find out.23“The Cipher Dispatches,” p.40 The electoral commission devised to settle the disputed electoral votes awarded all three Oregon votes to Hayes, as well as the disputed votes in the other states. But the cost of those votes was even steeper.

To settle the election and place Hayes in the White House free of any encumbrance, Republicans agreed to sell out the country and end Reconstruction. Federal troops would be removed from the South. Jim Crow laws would soon follow. It’s not to say that Tilden would have been better – beholden as he was to a party that was full of people who were recently traitors – but that Hayes ultimately placed the dagger in the heart of civil rights for nearly a century is beyond dispute.

Patrick’s role in all of this is largely forgotten to history, in large part because he was unsuccessful. Rosewater certainly never forgot, invoking Patrick’s name whenever possible to attack Church Howe, adding the additional charge that Howe meant to deliver Nebraska’s electoral votes to Tilden. The Advertiser, similarly hostile towards Howe, would often bring up Patrick’s name in connection with Howe as well. But Howe’s allies at the Journal believed Howe was fully vindicated in the Rosewater investigation, and Patrick’s friends at the Herald wouldn’t dream of attacking him, particularly given Miller’s ties.

John Nelson Hays Patrick died on January 30, 1905 at his home in Happy Hollow. The glowing obituary in the Omaha World-Herald only made passing mention of his time in the Nebraska Legislature, focusing mainly on his business and society life.24“J.N.H. Patrick Dies At His Home In Happy Hollow,” Omaha World-Herald, Jan. 30, 1905. The story of Lincoln’s naming was something that future historians would bring up, but the man behind it remained a name. The messier parts faded into memory, and we were left with just another story.