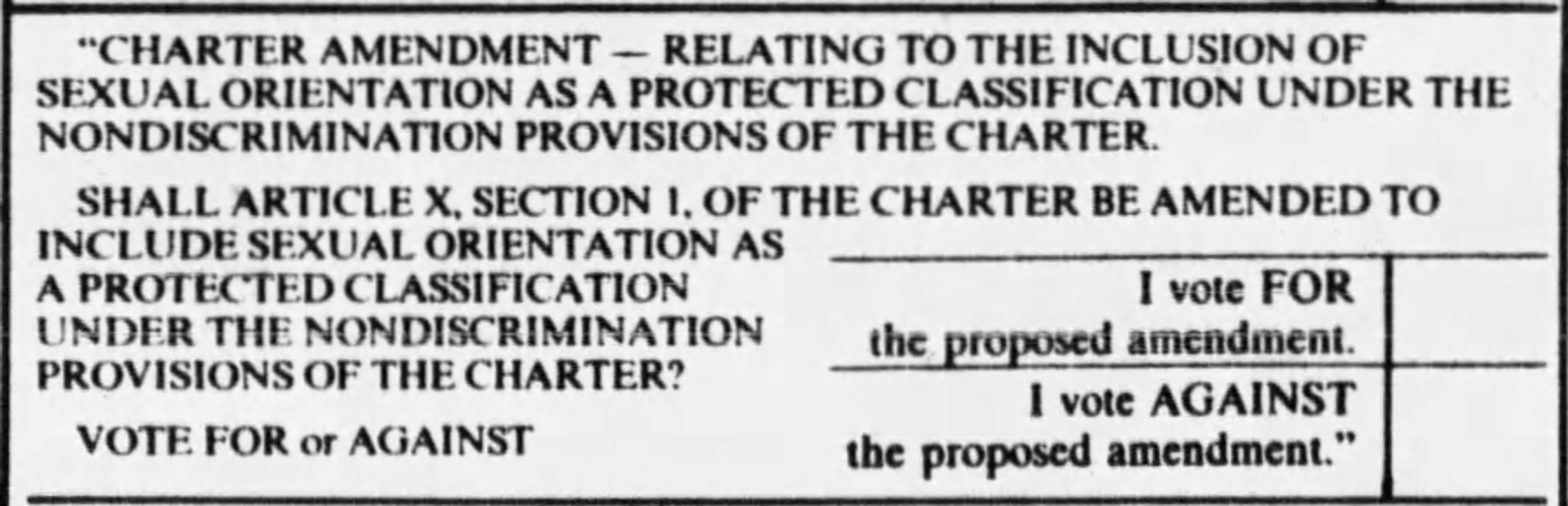

Days before Lincoln was to vote on a City Charter amendment that would add sexual orientation to the list of protected classes under the Lincoln Human Rights Ordinance, the leading opponent of the proposal made an explosive charge.

“Right now, here in Lincoln, there is a 4-year-old boy who has had his genitals almost severed from his body at Gateway [Shopping Center] in the rest room with a homosexual act,” Paul Cameron, chairman of the Committee to Oppose Special Rights for Homosexuals, told a church audience in Lincoln just over a week before the May 1982 primary election.1Kathryn Haugstatter, “Cameron Used False Report,” Lincoln Star, May 8, 1982. It wasn’t true. Cameron, who would later go on to found the Family Research Institute,2Paul Cameron | Southern Poverty Law Center admitted that it was a rumor. Lincoln Police said no such incident had occurred. But the outrageous rhetoric had its intended effect: the charter amendment failed by a nearly 4-to-1 margin.3Steven Stingley, “Gay Rights Advocates Say Issue Not Dead in Lincoln,” Omaha World-Herald, May 12, 1982.

The push to amend Lincoln’s anti-discrimination laws to include sexual orientation reached Lincoln’s government in 1981. Proponents organized a campus event at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln to help garner support for the measure, which first had to be approved by the Lincoln Human Rights Commission.4Kent Warneke, “Panelists Support Gays’ Civil Rights,” Lincoln Journal, Oct. 9, 1981. Immediately, there were problems. The Lincoln City Attorney’s office took the position that any such change would require either a change to statute at the statewide level, or a change to the City Charter, which would require a vote of the people.5Haugstatter, “Panel debates gay ordinance,” Lincoln Star, Oct. 9, 1981. Three decades later, Nebraska Attorney General Jon Bruning, then himself a candidate for U.S. Senate in the Republican primary, would rely on that opinion to argue that Lincoln must submit a similar proposal to the voters as a charter amendment.6Nancy Hicks, “Undeterred by AG’s opinion, City Council will consider anti-discrimination ordinance,” Lincoln Journal Star, May 4, 2012.

Proponents pressed on, and the Lincoln Human Rights Commission held a public hearing on the proposed changes. In addition to the standard inflammatory moral rhetoric, opponents argued that the changes would protect people who engage in illegal activity, as sodomy was a crime in Nebraska.7George Hendrix, “Gay rights law debated,” Lincoln Star, Nov. 18, 1981. Lincoln Mayor Helen Boosalis said she would sign the measure if the City Council passed it.8“Boosalis has ‘no qualms’ about ratifying gay rights,” Lincoln Star, Nov. 19, 1981. The Commission made a unanimous recommendation to the City Council in favor of the amendment.9Hendrix, “Gay rights get panel support,” Lincoln Star, Dec. 2, 1981. Commission member Bob Kerrey, who would be a candidate for Governor in the upcoming election, would face criticism even from members of his own party for his vote.10“Gay Issue Stand Under Attack,” Omaha World-Herald, May 7, 1982.

But despite the support of the Human Rights Commission and Mayor Boosalis, the City Council delayed.11Hendrix, “Council delays voting on gay rights proposal,” Lincoln Star, Jan. 5, 1982. The City Attorney’s opinion provided the Council with the only excuse some members would need to avoid taking a controversial stand. They could punt the question to the voters, if they decided to take action at all. The Human Rights Commission again urged the Council to act, voting to request the Council to conduct a public hearing on the ordinance.”12L. Kent Wolgamott, “Rights Commission renews pressure for gay rights law,” Lincoln Journal, Jan. 6, 1982. The Nebraska Attorney General issued an opinion supporting Lincoln’s legal authority to pass an ordinance.13“Gays Applaud Legal Opinion,” Associated Press, Jan. 8, 1982. But the City Attorney’s office stood by its opinion, and the City Council decided to hold a hearing to place the measure on the ballot.14“Council to discuss scheduling gay rights vote,” Lincoln Journal, Feb. 2, 1982.

The public hearing on the proposal took place on March 1 and lasted for six hours. Roughly an hour before the meeting was scheduled to begin, the city received a threat stating that a bomb would go off during the meeting at 8 p.m.15David Swartzlander, “Sexual orientation amendment on May ballot,” Lincoln Journal, Mar. 2, 1982. Law enforcement cleared the building to search for an explosive device, but found nothing. Many people who showed up for the hearing did not remain after the search, and fewer still remained for the entire six-hour meeting. The final vote came after midnight.

With only two months to organize, proponents of the measure faced a steep uphill battle. Cameron organized a letter-writing campaign to create the appearance of opposition in the local newspapers.16“Group to campaign against gay rights,” Lincoln Star, Mar. 9, 1982. The letters were full of vile bigotry and homophobia with the veneer of religiosity. “Bias must exist in law in order that a society can preserve itself, and protect its citizens against harm,” one letter argued.17Douglas W. Mueller, “Bias must exist,” Lincoln Star, Mar. 17, 1982. “God declared the same penalty for homosexuality as for murder – death,” another wrote.18J. Wendel Howsden, “No approval,” Lincoln Star, Mar. 17, 1982. “Citizens for human rights should be dealing with people who are human,” one Omaha letter said, “not homosexuals.”19Thomas Anthony Fleming, “Lincoln, the Gay Capital?,” Omaha World-Herald, Apr. 16, 1982. The campaign itself took to making false and outrageous claims, like the mutilated child. They claimed the amendment would force businesses to hire homosexuals through affirmative action programs, and would provide protection against prosecution for rape, sodomy, and incest.20“Gay rights opponents’ ‘facts’ said wrong,” Lincoln Star, Mar. 18, 1982.

Proponents, meanwhile, failed to gain mainstream support. The Democratic Party was far from decided on the issue. Kerrey’s opponent in the primary election criticized him for supporting the proposal. DiAnna Schimek, then the leader of the Democratic Party, answered Republican criticism of the proposal by calling the matter “a local concern.”21“Republican Official Asks for Stand on Gays,” Associated Press, May 6, 1982. The Lincoln Chamber of Commerce opposed the amendment, citing the increased burdens they claimed it would place on businesses.22“Chamber supports jail bond issue,” Lincoln Star, Apr. 16, 1982. A poll conducted the week before the election showed the measure trailing 53-34.23Swartzlander, “Pollster: Gay rights measure won’t pass,” Lincoln Star, May 9, 1982. Ultimately, the proposal lost 78-22.

Opponents were jubilant at such a resounding victory. Some sought to press the advantage. “If Lincoln is to remain a nice Christian city… the Christians of this city must become more involved in politics other than on election day,” one op-ed in the Lincoln Journal said.24Doug Wehrli, “Must keep Lincoln a nice Christian city,” Lincoln Journal, May 19, 1982. But if there were any electoral ramifications for those who supported the proposal, they weren’t readily apparent. Bob Kerrey would go on to win the election for Governor in 1982, and later would go on to serve two terms as a U.S. Senator. Helen Boosalis was the Democratic nominee for Governor four years later when Kerrey declined to run for reelection. Proponents of the measure put on a brave face, calling the vote a “first step.”25Stingley, “Gay Rights Advocates Say Issue Not Dead in Lincoln,” Omaha World-Herald, May 12, 1982. But it would be a decade before a serious anti-discrimination proposal next arrived.